Dividend Growth Investing is about purchasing dividend stocks that grow their dividends over time, and then holding onto those investments for quite a while as you receive continually increasing passive income from those companies.

Why this strategy? Because it gives you passive income that grows exponentially each year, and simultaneously builds your net worth over the long-term. Wealth is not simply about having a lot of assets, it’s about generating a significant amount of passive income that grows over time. Dividend Growth Investing works to build both your passive income and your net worth, can be more reliable than other investing methods, requires less time, and can be performed by anyone with sufficient discipline and basic math skills.

Dividend Growth Investing is not just about investing in stocks with a high dividend; it’s also about investing in companies that grow their dividends year after year. A passive income stream is typically unimpressive if it doesn’t grow. By investing in dividend growth companies, you’ll be building passive streams of income that grow over time. Each year with this investment strategy, assuming your companies stay healthy and profitable, your dividend passive income will increase. Better yet, unless you’re planning on living off of your dividends right now, you can reinvest your dividends to buy more dividend paying stocks to further increase your passive income. The growth is exponential, and the strategy works over a long period of time to build your wealth.

Companies that Pay Dividends

When a company makes a profit, they have several options for what they can use that money for. They can reinvest it to grow their business, save it for a rainy day or pay off debt, or send it to shareholders as dividends or share repurchases. Many companies use it for a combination of those things. Of the various public companies in existence, a significant subset of them pay regular cash dividends to shareholders. Regular dividends are cash payments that shareholders receive by simply holding the stock. Shareholders can then spend these dividends any way that they could spend any other form of cash income. It can be used as current income or it can be used to reinvest and buy more shares. The share can be held indefinitely, receiving income year after year.

Dividend Terms to Know

Dividend Yield

A share represents a portion of a company, and a dividend represents that shareholder’s portion of distributed earnings from that company. The dividend yield is equal to the annual dividends paid per share divided by the share price. For example, if I buy a share of a company for $50, and that share pays me a $2 cash dividend this year, then my dividend yield is 4%. Using the same math, if I spend $5,000 to buy 100 of those $50 shares, and those shares offer a dividend yield of 4%, then my annual dividends (passive cash income), will be $200.

Dividend Growth Rate

Dividend Growth Investing is not merely concerned with how much passive income your shares give you, but also how quickly that passive income grows. Many companies increase their dividend payments each year, meaning that each year’s passive income is larger than the year before it. Several companies have records of paying increasing dividends for 10, 25, or 50 consecutive years in a row and are still continuing with this trend. Some people look at a dividend yield and mistakenly assume this will be their total rate of return, but that is not the case. Dividend growth must be factored in as well. If a company pays $1 in dividends per share this year, $1.1 in dividends per share next year, $1.21 in dividends next year, then it is currently growing its dividend at a rate of 10% per year on average. If this continues for 30 years, then the company will be paying over $17 per year in dividends per share at that time! Exponential growth is enormously powerful.

Dividend Payout Ratio

The dividend payout ratio is the percentage of per-share earnings that are paid out as dividends each year. So if a company has earnings-per-share (EPS) of $3, and pays out $1 in dividends per share this year, then the payout ratio is approximately 33%. The company is paying out a third of its profit to shareholders as dividends, and keeping the other two-thirds of its profit for other purposes such as growing the business, making acquisitions, reducing debt levels, or repurchasing shares. It’s important to know the payout ratio because it gives you an idea of the growth prospects of the company, and lets you know whether the dividend is safe. If the company doesn’t have enough earnings to keep up with its dividend payments, it will have to reduce its dividend, and we certainly don’t want that.

The Math Behind Dividend Growth Investing

I’ll use a fictional company called Monk Mart Inc. as my example throughout this section. Monk Mart stock currently trades for $30 per share and has a price-to-earnings ratio (P/E) of 12. So, EPS this year is $2.50. Monk Mart currently has a payout ratio of 40%, so the company is paying out $1.00 in dividends to each shareholder this year. Using these numbers, it is calculated that Monk Mart’s dividend yield is 3.33%. Furthermore, Monk Mart currently has plans to increase the dividend by 8% annually by growing its business.

Monk Mart is a stock that increases its dividend approximately in line with its EPS. If the dividend grows by 8% each year, and the payout ratio remains 40% and the P/E remains 12, that means that the stock price will also increase by 8% each year. Of course, in reality, the stock price won’t increase at exactly the same pace as the dividend payments, because the payout ratio or P/E may fluctuate in times of bull markets and bear markets. To keep the calculations for reinvested dividends manageable, I’m going to assume that Monk Mart stock continually has a P/E of 12 and a payout ratio of 40%, along with 8% dividend growth.

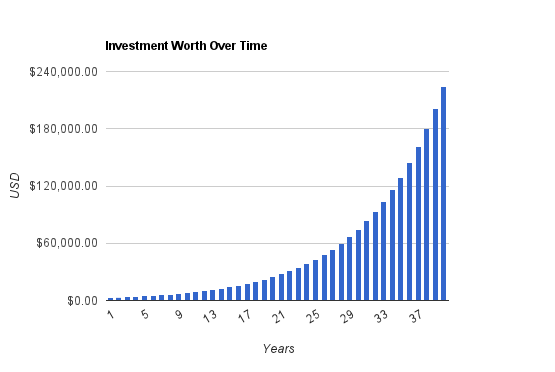

In this scenario, I’m going to purchase 100 shares of Monk Mart stock for $30 each, for a total of $3,000. This means that I’ll receive $100 in dividend payments this year. My plan is to reinvest all of my dividends into buying more Monk Mart stock. I have the stock in a non-taxed retirement account, and my broker allows me to reinvest dividends to buy more shares (including fractions of shares) without charge. Let’s see how much much value my Monk Mart stock returns to me.

During year 1, I collect my $100 in dividend payments. I use them to purchase more shares, so at $30 per share I can purchase an additional 3.33 shares and now have a total of 103.33 shares of Monk Mart. My investment is now worth $3100.

During year 2, Monk Mart indeed raises its dividend by 8% from $1.00 per share to $1.08 per share, and because the P/E and payout ratio remained static, the stock price is now $32.40 per share. Since I receive $1.08 per share in dividends this year and have 103.33 shares, my total dividend income this year is $111.60, and I’ll use that money to buy more shares at $32.40 per share. So, I use my $111.60 to purchase 3.44 shares and now have 106.77 shares of Monk Mart. My investment is now worth $3459.35.

During year 3, Monk Mart again raises its dividend by 8% from $1.08 to $1.17 per share, and because the P/E and payout ratio remained static, the stock price is now $34.99 per share. Since I receive $1.17 per share in dividends this year and have 106.77 shares, my total dividend income this year is $124.92, and I’ll use that money to buy more shares at $34.99 per share. So I use my $124.92 to purchase 3.57 shares and now have 110.34 shares of Monk Mart. My investment is now worth $3860.80.

And so on. It may sound like a lot of work, but many brokers allow you to automatically reinvest your dividends leaving very little maintenance for the investor.

After 10 years, the investor owns 134 shares, the total investment is worth over $8,300, and the dividend income is more than $268/year.

After 20 years, the investor owns 186 shares, the total investment is worth over $22,300, and the dividend income is more than $804/year.

After 30 years, the investor owns 258 shares, the total investment is worth over $74,700, and the dividend income is more than $2,400/year.

After 40 years, the investor owns 359 shares, the total investment is worth over $224,000, and the dividend income is more than $7,200/year.

In this scenario, a mere $3,000 turned into more than $224,000 40 years later, and a mere $100 in annual dividend income turned into more than $7000. Both the investment worth and the passive dividend income grew at a rate of return of more than 11%. There will of course be inflation, so the money in the future will have less purchasing power than it does today, but it’s still a whole lot more money than there was to begin with. In addition, stocks are fairly inflation-resistant because a good company can pass the costs of inflation onto its customers. And, this large growth of money only represents a single investment. If the same investment of a few thousand dollars was made each year, then the investment worth would be worth millions by the end.

Notice again that the total rate of return of investment worth in this example was a little over 11% per year. If you add the dividend yield (3.33%) to the dividend growth rate (8%), you’ll get 11.33%, which is the approximate rate of return of this investment. It’s a good rule of thumb that all else being equal, the long-term dividend yield plus the long-term dividend growth rate is what you can expect in terms of total return. In reality, the P/E won’t stay static, and other factors will fluctuate. If you let this work against you, the return may be somewhat less than the yield plus the growth, but if you work it in your favor, the return may be somewhat more than the yield plus the growth.

A huge portion of the returns of this stock were due to dividends. If dividends were not reinvested, then instead of owning 371 shares at the end, the investor would still only own 100. Since each share was worth approximately $600 by the end, the investor would only have had an investment worth of approximately $60,000 rather than $224,000.

Passive Income Growth and Re-Investing

As previously mentioned, the goal of this investment approach is to simultaneously build passive income and a high net worth. A company has control over how much it pays in dividends, but the masses of the market are the ones that determine the stock price at any given time, so the company growth and the dividends they pay are the primary points of focus for dividend growth investors. Stock prices fluctuate all the time, going up and down, but a disciplined company can grow its dividend year after year without missing a beat for decades. It’s important to have a disciplined mindset, because in the real world even if a dividend-paying company provides long-term returns similar to those in my Monk Mart example, the growth will never be that smooth and the market will sometimes reduce the value of your investment. A dividend investor’s job is to pick good companies to invest in at reasonable stock valuations, with both money they put into their portfolio and money they receive as dividends.

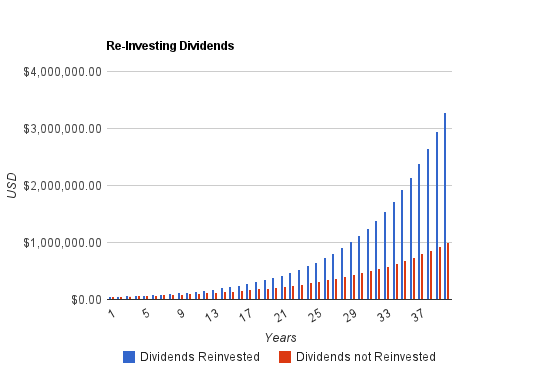

To maximize investment returns, the investor should use the dividends they receive to purchase more shares, like with the earlier Monk Mart example. Consider the following chart, which displays a comparison between reinvesting and not reinvesting dividends in a given company. In the chart, two investors start out with $50,000 and keep the money invested for 40 years. The company that they invest in pays out a 3.33% dividend yield and grows its dividend at an 8% rate annually. One of the investors spends his dividends while the other investor reinvests her dividends to buy more shares.

Over time, the investor that reinvested dividends accumulated more shares of the company, so her investment worth increased at a higher rate. She ended up with over $3 million while the investor that did not reinvest dividends only ended up with $1 million.

Eventually, a person can live off of their dividends as current income rather than reinvesting them. If enough value is accumulated, the passive income will be high enough so that no shares ever have to be sold, and so the investor can live off of his or her accumulated wealth indefinitely while continuing to grow, rather than shrink, their net worth.

Characteristics of a Good Dividend Investment

Obviously, the dividend growth strategy takes time and discipline. We need to identify companies that will provide good returns over decades. No single investment must last for the entire span of the investor’s life, because the investor ideally has a diversified portfolio of several dividend-paying companies, but the better the investments perform over the long-term, the lower the turn-over rate of the portfolio needs to be. Some good selections might last throughout the entire span of the investor’s life.

There is no set formula for finding a good dividend growth stock for your portfolio. I leave formulas for the technical speculators. There are, however, general principles that are worth looking for in investments.

-A good dividend growth company has a product or service that you can foresee existing and being relevant for many decades to come. Time is very important to allow passive income to increase, so it’s wise to find a company that is built to last forever.

-The company should have unique aspects that separate it from competitors.

-A strong balance sheet is the hallmark of a good dividend investment, because it increases the chances of your company being able to survive and grow.

-Keep in mind the general estimation that the total rate of return will be equal to the dividend yield plus the sustained dividend growth rate. Some investors like high-yielding stocks with lower dividend growth while others like lower-yielding stocks with higher dividend growth, and some prefer a mix of both, but keep this basic guideline in mind.

-The company’s stock should be reasonably priced. A good company can make a bad stock if it is over-priced relative to its fundamental value. If you buy stock in an overvalued company, your returns are likely to be less than the sum of dividend yield and dividend growth. If, instead, you buy quality undervalued companies, your returns may be greater than the sum of dividend yield and dividend growth.

-You should be able to understand the company. My view of investing is about individuals taking control of their finances, so if they don’t really understand their stocks, they aren’t really taking control of their finances.

I know how hard it is to invest when stocks don’t seem to trade at their fair value

Don’t you hate not knowing when to buy or sell stocks? There are too many investing articles contradicting one another. This creates confusion and leaves you with the impression you will not reach financial independence. It doesn’t have to be this way. I’ve built a free recession-proof portfolio workbook which will give you the actionable tools you need to invest with confidence and reach financial freedom.

This workbook is a guide to help you achieve three things:

- Invest with conviction and address directly your buy/sell questions.

- Build and manage your portfolio through difficult times.

- Enjoy your retirement.

Good post, especially the graphs about reinvested dividends and the importance of growing dividends.

I wrote a post about reinvested dividends a couple of days ago but your graphs are much clearer. Here we can visually see the difference between the alternatives.

Is it ok if I quote two sections from this post into my article? I will of course mention your name.

Dividend growth investing is one of the best strategies for investing. About half my portfolio contains stocks like this. Even better, if you took advantage of the cheap prices recently. You could have bought excellent companies like Conoco Phillips and got a yield of over 5% plus this company has a solid history of raising their dividend…in fact they did so just recently. If compound interest is the 8th wonder of the world, then dividend growth investing is the 9th, I’m a solid believer in it. Great post Dividend Monk!

Hey Monk,

You may or may not know, I follow your site, but do not leave many comments. I do however, feel compelled today to leave one after reading this post. AMAZING work!

Cheers,

My Own Advisor

Thanks for the positive feedback. I spent a good deal of time on this post and have had it sitting in my drafts section for weeks now, and I intend to put it on the “start here” section as a core article for the site. I plan to update it and improve it as necessary.

defensiven,

Yes, please feel free to quote whatever you wish to.

I stopped by after following the comment you left on my site, and I agree, this is amazing work. A dividend-based approach to investing can definitely be a core component of an infinite portfolio. I love the graphs as well; you did them with Google Spreadsheet? They are really nice; much better than what you get with Excel or OpenOffice.

As some food for thought, have you compared and contrasted dividend investing as opposed to capital growth? Why would selling shares be a bad thing if you were selling an amount in dollar terms equivalent to the amount of dividends that you would be collecting? If the overall rate of return were the same, wouldn’t not reinvesting dividends be the same thing as selling shares in a stock or index that reinvests this cash internally? Have you written about this? I’d be interested in reading more.

Invest it Wisely,

Yes, I did the graphs with Google spreadsheet. They’re really handy, but the ability to customize them is significantly less than Excel. I’ve never used Open Office so I can’t compare there.

Over the long-term, dividend-paying stocks have been shown to outperform non-dividend paying stocks on average. Of course there are exceptions, so a diversified portfolio is necessary. This is because most companies can only invest so much money into growth until more money won’t help much that year, so it ends up being wasted on poor projects. Selling stocks of a dividend-paying company isn’t helpful unless you no longer consider that investment to be worthwhile, because as you hold onto the stocks, capital appreciation should occur as long as things are going well. The more portfolio turnover there is, the more that is lost to taxes.

It’s true that, for example, if a dividend-paying company has 8% growth and a 3% yield while another company has 11% growth over the same period, the returns of the companies will be comparable. But, often this is not the case, and a dividend paying company ends up growing just as well as the one that wastes its money on other things. Its dividend, then, ends up being crucial to its out-performance.

Hate to be such a “Dividend Monk Fanboy,” Matt, but this was quite possibly the best post I’ve ever come across on the subject. It’s written very clearly and is laid out in a simple, easy-to-understand way.

Again, keep up the good work!

Thanks Pey, I appreciate your continued readership.

Matt,

This is also my first time visiting your blog, and like the other readers, I’m very impressed.

I do have one thought about reinvested dividends vs money being allocated internally. If a company has proven that it can average a high return on total capital within the majority of its business operations(averaging, say, 15%+ per year for many years) then the company can reinvest what would be dividends, and thus save the shareholder tax. I’ve read two very interesting books on this: Jeremy Siegel’s book, The Future for Investors, where his philosophy is in line with yours. And then I read a book by Brian McNiven, called A Great Company at a Fair Price.

Siegel, as great as his book is, ignores taxable consequences of dividends. And as Buffett has said, dividends are taxed twice: once at the corporate level and again at the personal level. Even when reinvested (if it’s a taxable account) the taxable liability still takes a hefty chunk.

McNiven’s philosophy opposes Sielgel’s. He suggests that if the company is purchased at a fair price (and not a dumb price) then the company with the higher rate of return on capital can utilize that money much more effectively, and as such, the company’s share price will grow faster than it will with the higher dividend paying business. And that share price grows capital gains free until sold.

Buffett himself leans more towards non dividend payers–but there’s a twist.

We know that Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway hasn’t paid a dividend in more than 30 years because Buffett feels that the return on capital that he generates by retaining those earnings will create eventual share price appreciation value for the shareholder that will exceed the share price/dividend capital appreciation that his shareholders would receive. In his view, paying out a dividend and then reinvesting it back into the business (reinvesting the dividend) does virtually the same thing, but the shareholder holds on to the tax bill in the process.

The other thing Buffett mentions, however, is probably the key that separates a Warren Buffett from a guy like me. First of all, now that Berkshire is so huge, he has to buy many large companies that pay dividends. But he prefers smaller businesses that effectively retain their earnings. But he just can’t buy those anymore. They don’t move Berkshire’s needle.

A guy like Buffett can look at the return on total capital and determine whether all of the money is reinvested in parts of the business with high returns. Investors like me would just see the average return on capital, suggest that it’s high, and figure that the business is more efficient as a non dividend (or low dividend) payer. Meanwhile, the business could be wasting money, as you alluded to in your comment to Kevin. In Buffett’s 1983 letter to shareholder’s he said, “Shareholders are better off only if earnings are retained to expand the high-return business…Managers of high return businesses who consistently emply much of the cash thrown off by those businesses in other ventures with low returns should be held to account for those allocation decisions” That was a nice way of say, “they should be fired”

Kevin, if I’m reading you correctly, you’re curious about whether the investment should be sold—in pieces equivalent to what the investor would receive from dividends. Doing so might negate the power of those compounding dividends, throwing off more dividends as new shares are purchased. But I don’t really have an answer.

Great post – lots of good analysis and data in there. New income investors are often drawn to high yields like moths to the flame without considering why those trailing yields are showing so high. It’s generally better (and safer) to target dividend growth over current yield.

Andrew,

That’s quite a comment!

I agree that in a rare case where a business truly can utilize all of its cash effectively, a dividend is not necessary. Buffett certainly meets that criteria. The thing with Berkshire, though, is that it’s a conglomerate that can buy pretty much whatever it wants. It has an effectively unlimited number of places to allocate capital, and with Buffett at the top, that’s a fantastic combination.

Most businesses are confined to a certain niche, with finite opportunities. Most businesses don’t do well by “empire building”, that is, growing simply for the sake of growing without a focus on total shareholder returns. The majority of companies out there would do well to pay a dividend.

Tax consequences are important, but it’s also true that many holdings are held in tax-free accounts amassed in retirement accounts in various countries.

Lastly, by not paying dividends, shareholder returns are entirely due to stock market price, which is continually set by the whim of the market. Dividends allow shareholders to make a decision, with their own personal circumstances in mind, about how they want to allocate this part of their capital. They can reinvest them, spend them, invest them in another company, put them into a different type of asset, etc. It’s an additional tool to deal with a variety of market conditions. Personally, I let my dividends pool together and then decide where I’m going to allocate them, along with fresh capital to my portfolio.

Darwin,

Thanks for stopping by. I agree with what you’ve said. Although I enjoy finding attractive high-yield investments from time to time, I find that attractive moderate-yield investments tend to come along more often.

Great explanation and graphs of dividend reinvesting. Using your example of Monk Mart, the dividends are steady and growing year to year. However the share price (and therefore dividend yield) may fluctuate depending on investor psychology. Reinvesting the dividend in each company will be a from of dollar cost averaging which is an advantageous tactic. However, what if the dividends were collected among all the investments in a portfolio and reinvested in those companies whose share price is transiently lower to maximize the total return?

Hi Frank,

That’s how I do it, personally. I collect all of my dividends in a pool and invest them where I find good deals.